(This story was originally published in Maxfighting.com)

By Frank Forza Curreri

LAS VEGAS, Nev. — Come Saturday morning, Dewey Cooper expects to walk into a room at Kindred Hospital and address his father. Barring a miracle, it will be one-way conversation.

Floyd Cooper, a decorated Vietnam veteran who made a habit of never showing weakness, can only perform three moves: He can move his eyes. He can blink. His fingers involuntarily tremble. A stroke on Feb. 1 has robbed the 60-year-old of everything else.

“My Dad – I’ve never seen him like that,” Cooper said recently from his Las Vegas home. “It freaked me out. We take everything for granted. I just took for granted, you know – my Dad is a mean, strong, big man who can’t be dominated and he’s going to be like that forever.”

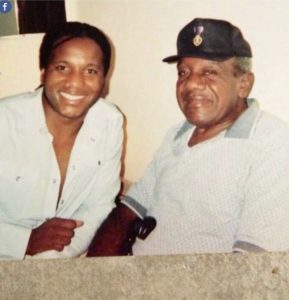

Pro fighter Dewey Cooper poses with his father, Floyd Cooper, a Vietnam veteran. Photo courtesy of Dewey Cooper.

If all goes as planned for Dewey Cooper during Friday night’s Battle at the Bellagio K-1 tournament, the grossly undersized heavyweight will topple three Goliaths and claim his first K-1 title.

When it’s all over, his legs will feel like they have been repeatedly pounded with a stick, and he will barely be able to walk for a week after the event. But those wobbly legs will lead him to his father’s bedside, where Dewey Cooper hopes to say: “Daddy, I did it.“

Interestingly, no matter how heavy-hearted pugilists like Dewey Cooper are, they rarely back out of fights. History has shown that such combatants, rather than shrinking due to sorrow, usually become more dangerous in the ring. Shortly after his mother’s death, a 39 to 1 underdog named Buster Douglas did what no one believed anyone on the planet could do: he knocked out Mike Tyson.

On April 10, heavyweight boxer Lamon Brewster – a virtual no-name whom even many seasoned journalists had never heard of – walked down the aisle carrying a picture of his late trainer Bill Slayton, who had died a few months earlier. Like Douglas, Brewster’s heart and determination had been questioned until then. But the Los Angeles fighter fought as if he were willing to die in the ring, absorbing a tremendous beating before stopping Wladimir Klitchko for the WBO title.

Cooper, however, has also seen tragedy cripple a fighter’s will. He was the last person to spar with journeyman boxer Brad Rone in July 2003. Rone, a happy-go-lucky sort whose mother had died July 17, fought in Utah the following day so he could pay for a plane ticket back to Ohio to attend her funeral. Rone collapsed in the ring at the end of the first round and never regained consciousness.

An autopsy pinpointed cardiac arrest as the cause of death, but many believe Rone died from something autopsy results can not detect: a broken heart.

Cooper shakes his head in disbelief as he recalls the fate of his late friend. In his particular case, Cooper predicts that his father’s predicament will be empowering, not diminishing.

“That extra motivation – that might be what I need to get me over the hump and win the whole damn tournament,” said Cooper, who has a combined pro boxing and kickboxing record of 37-6 with 24 knockouts.

The “Black Kobra” is one of the most complex souls in the fight game today, an enigma whose core identity seems elusive and easily misunderstood. The dreadlocks smack of Bob Marley, though his toughness and relatively small size – amazingly, Cooper has never been dropped by punches in his career – more closely resembles braided basketball star Allen Iverson. The lip and nose rings give him a touch of Dennis Rodman. He pulls no punches inside the ring nor out of it; Cooper has the relentless candor of a Warren Sapp, which is to say he is often eloquent and offensive in the same sentence.

Cooper hurled this zinger at mixed martial arts star Bob Sapp, a 375-pound former pro football player, “his pain tolerance has gone to the gutter. He has a glass chin. He ain’t (expletive).”

Cooper is unafraid to call out fighters he considers fakes, but professes to be a stickler for sportsmanship. Ringside ticket holders may see him jawing throughout his fights ala Muhammed Ali, but Cooper is merely talking to himself. During a recent training session in his garage on a sunny Saturday afternoon, Cooper pounded the mitts of boxing trainer Jeff Mayweather. His tongue stayed as busy as his hands.

“Ooooh, good stuff,” Cooper said, admiring one of his crisp combinations as a 50 Cent CD pumped in the background. “That was good hook, boy! I can train all damn day!”

Few sayings offer a greater boost to Cooper’s psyche than when he utters the initials ‘BK,’ which is short for his nickname.

“It makes me hyped,” Cooper said. “I get that warrior mindset.”

Watching Cooper, it is as if adrenaline decided to become a human being. When his fight persona is on display, he talks fast, kind of like the Gary Coleman character in Different Strokes when he said “Whatyoutalkin’aboutWillis?”

Tony Valente, Cooper’s conditioning coach and a K-1 pro veteran, says Cooper is a workaholic whom he must make leave the gym.

“He actually overdoes it,” Valente said. “He doesn’t know when to quit.”

As a result, Valente said, Cooper has a problem with peaking too early before fights. Jeff Mayweather, younger brother of Floyd Mayweather Sr. and a former world-ranked boxer and father to the notorious Floyd Jr., said Cooper’s supersized ego has been both a blessing and a curse. Like Evander Holyfield (a true cruiserweight turned heavyweight), Cooper has exceptional courage and had been willing to go toe-to-toe with any foe even when he was at a 40-pound weight disadvantage.

“Are you out of your mind?” Mayweather asked him two years ago. “If you keep fighting like this you’re going to take way too much punishment and your career is going to be five years instead of 15 years.”

So Cooper altered his fighting style, trading bravado for science. His blueprint for victory is now to hit without being hit, and he keeps busier with head movement and jabs.

Cooper doesn’t know much about his first-round opponent, Japan’s Nobu Hayashi (12-11 with 6 KO’s). Hayashi trains in Holland, widely regarded as the top producer of K-1 talent, and has tipped the scales at close to 245 pounds in recent fights. He was a finalist for a K-1 Grand Prix in 1999.

Cooper is accustomed to the weight disadvantage. At a mere 202 pounds, he is the smallest competitor in the eight-man field, which features Mighty Mo a 280-pound pro boxer and K-1 rookie and Stephan Gamlin, a 325-pounder who once played defensive tackle in NFL Europe.

During a fight last year at the Bellagio, many fans and journalists thought Cooper had upset former 2003 K-1 USA champion Carter Williams, who outweighed him by nearly 30 pounds. The judges handed the victory to Williams via unanimous decision.

Cooper’s natural fighting weight is 190 pounds, meaning he’s roughly the same size as all-time great boxer Roy Jones. Jones made history when he jumped from light heavyweight and manhandled John Ruiz en route to winning the WBA title last year. Otherwise, Jones had never banged with the big boys. Cooper routinely tests himself against men 30, 40 and 50 pounds larger and prevails. He is able to survive and conquer thanks to some of the fastest and most accurate hands in K-1, the most trusted being his devastating left hook.

“The strong man will always defeat the weak,” Jeff Mayweather likes to say. “But the smart man will always defeat the strong man.”

Almost every opponent uses the same strategy when they face Cooper: they constantly kick at his legs. Cooper journeyed to Thailand a month ago for pointers on how to defend those assaults, and hopes to be at his best when he clashes with Hayashi. The perpetual underdog still has something to prove.

“I don’t like feeling like people think that I don’t have a chance,” Cooper said. “I feel like they’re flying this guy 6,000 miles to rain on my parade. It’s very personal for me. I’m dedicating this fight to my Daddy, so I got to represent.”